Nipah

Nipah virus is one of the most lethal pathogens known to infect humans. Find out more about this pathogen and our R&D efforts in this disease area.

What is Nipah?

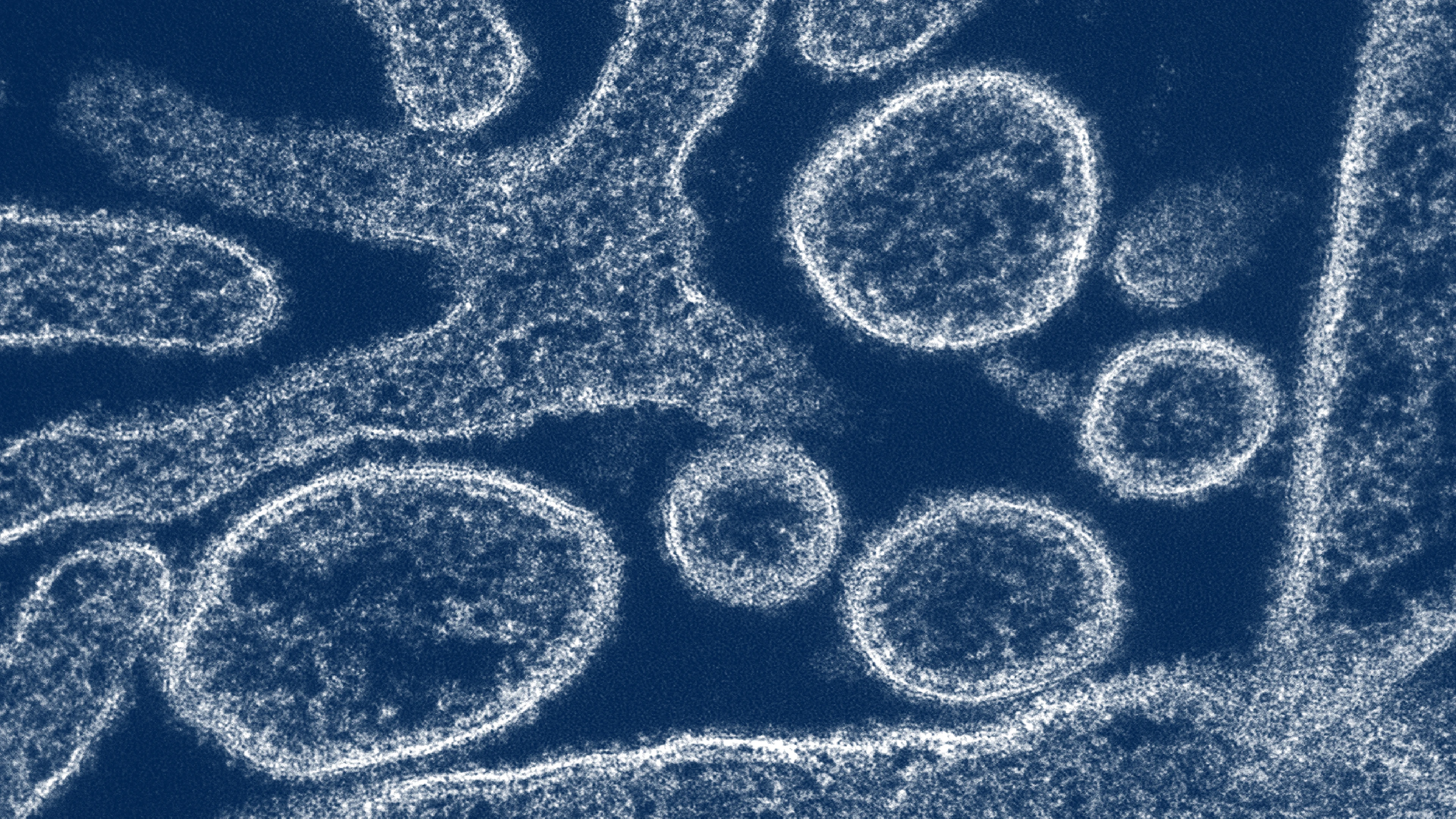

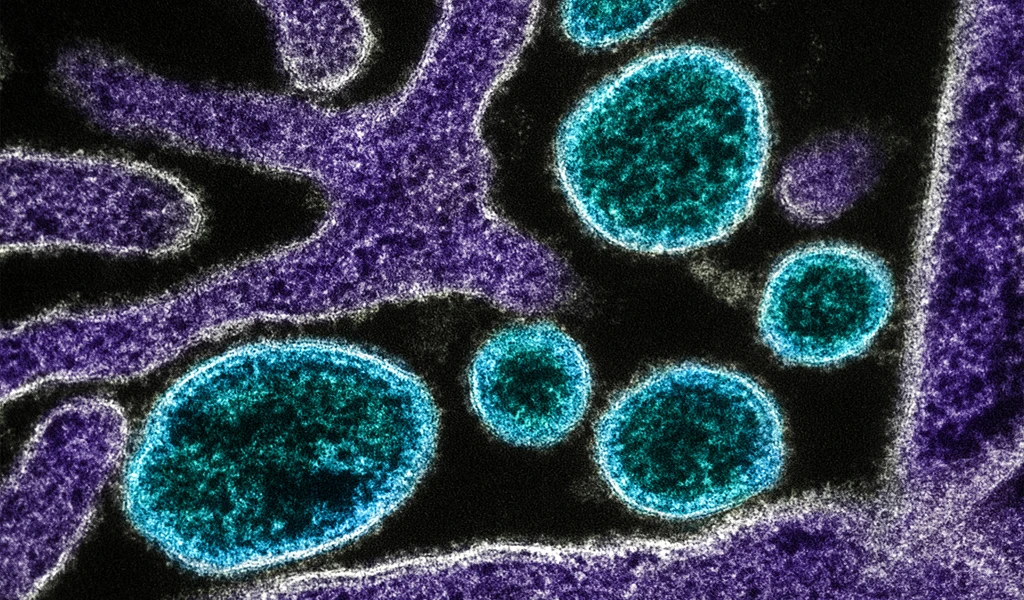

Nipah virus belongs to the Paramyxovirus family. It is one of the deadliest pathogens known to infect humans.

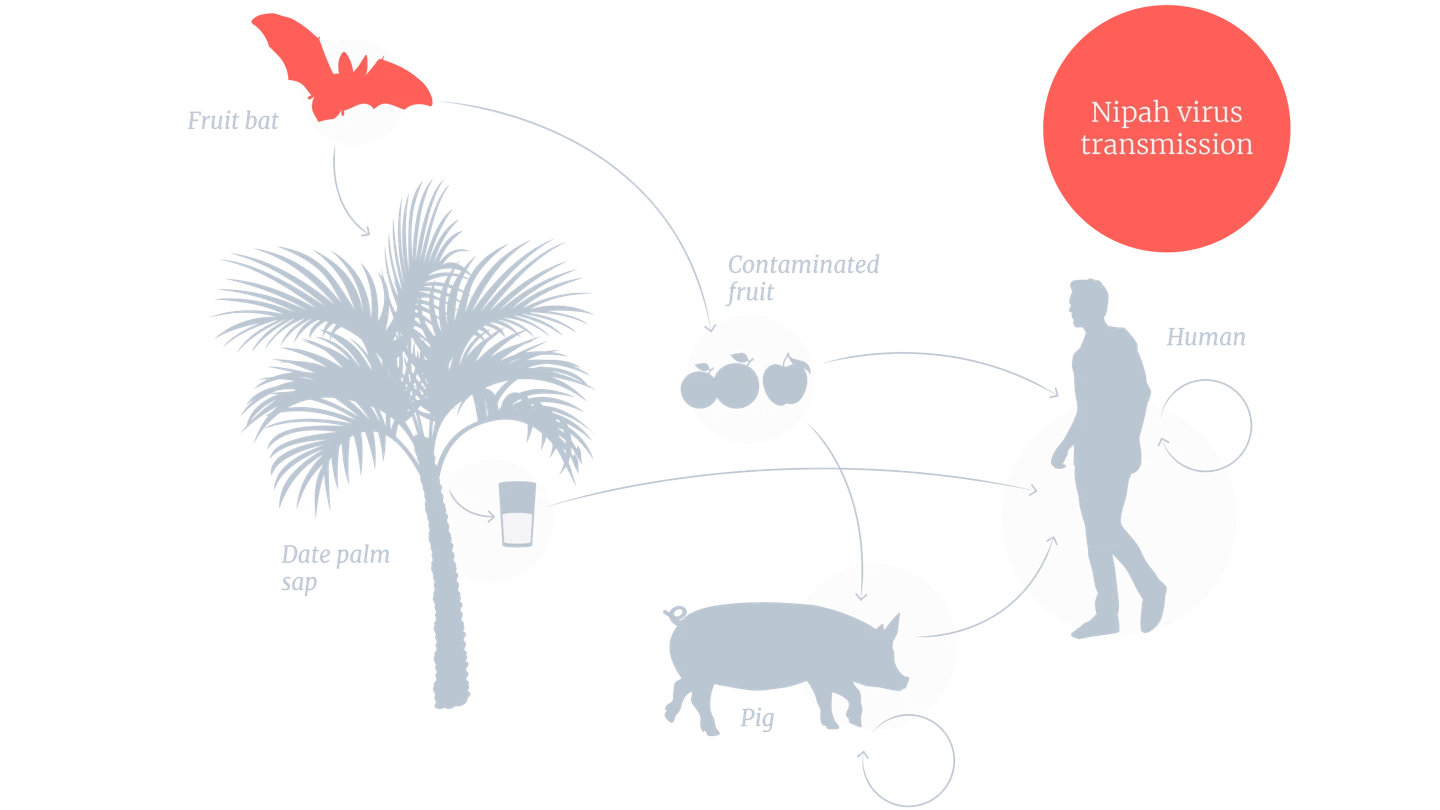

Nipah is a zoonotic disease, which means it passes from animals to humans. The natural hosts of the virus are fruit bats, also known as flying foxes.

Nipah virus can be spread to people from infected bats, infected pigs, or infected people.

Despite its notable epidemic potential and high fatality rate - being recognised as one of the priority pathogens on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) R&D Blueprint list - no safe and effective vaccines and therapeutics have been approved for human use.

Where does Nipah occur?

Nipah was first identified in 1999 during an outbreak of illness affecting pig farmers and others having close contact with pigs in Malaysia and Singapore. Over 100 human deaths were reported, and over a million pigs were killed in an effort to stop the outbreak. No cases of person-to-person spread were reported.

In 2001, there was an outbreak of Nipah virus in people in Bangladesh and a separate outbreak in a hospital in India. In both countries, person-to-person transmission occurred. Since then, Bangladesh has suffered outbreaks nearly every year from 2001 to 2024. India has also experienced occasional outbreaks.

So far, Nipah outbreaks have been confined to South and Southeast Asia, but the fruit-bat viral vector is found in a large geographical area across the globe covering a population of more than 2 billion people.

The increasing frequency of human encounters with fruit bats, the viral host, is expanding opportunities for Nipah virus transmission, heightening its outbreak potential. Recognised as a critical threat, Nipah is on the WHO’s R&D Blueprint list of epidemic threats needing urgent R&D action.

What are the symptoms of Nipah virus infection?

Nipah is a deadly disease that kills an estimated 40–75% or higher of those infected.

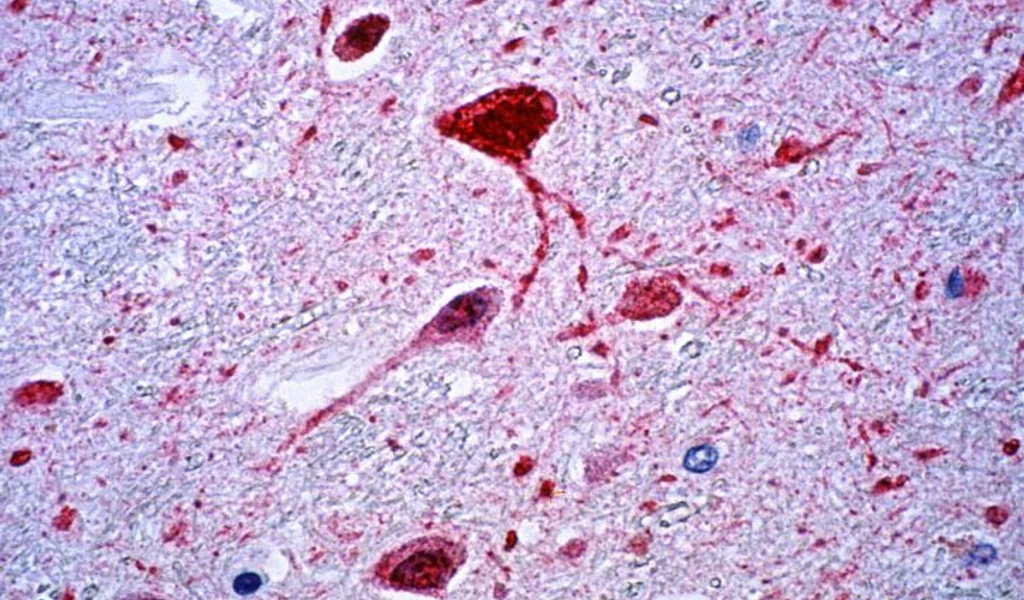

Nipah virus infection can cause severe, rapidly progressive illness that affects the respiratory system and the central nervous system, including inflammation of the brain (encephalitis).

Symptoms begin between 5 and 14 days after infection, and include fever, altered mental state, cough and respiratory problems.

Increasing age and respiratory symptoms have been identified as indicators of infectivity of Nipah virus.

There are currently no vaccines or specific therapeutics against Nipah virus approved for use in humans.

Given how lethal Nipah is and its epidemic potential, a range of countermeasures will be required to provide near-term and long-term protection, including diagnostics, vaccines, and monoclonal antibodies.

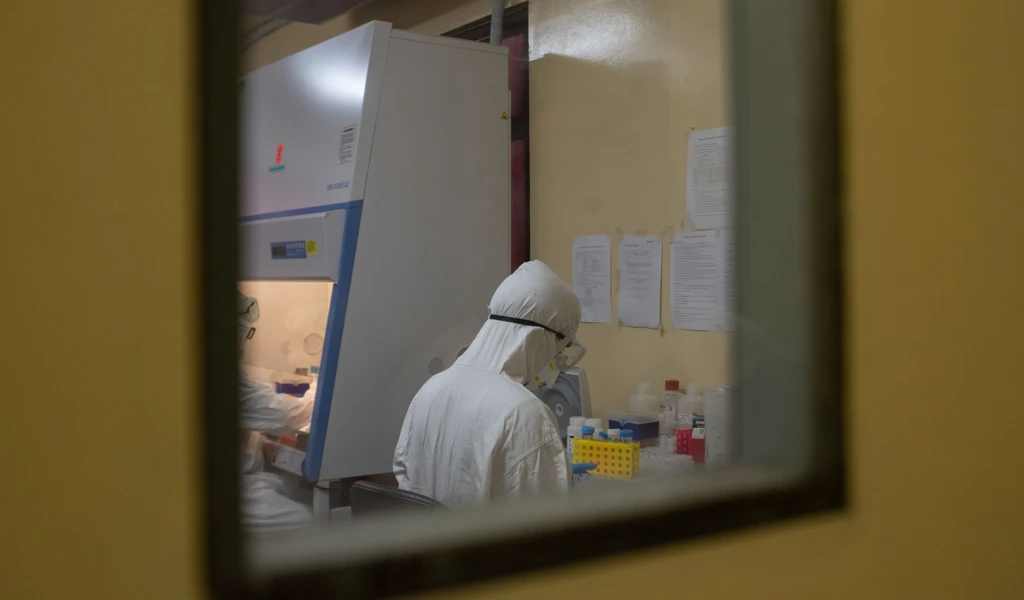

How is CEPI responding to Nipah?

CEPI is one of the largest funders of Nipah research, committing over US$100 million to its Nipah programmes. CEPI supports key R&D activities in affected countries that provide crucial epidemiological and immunological data to inform medical countermeasure development.

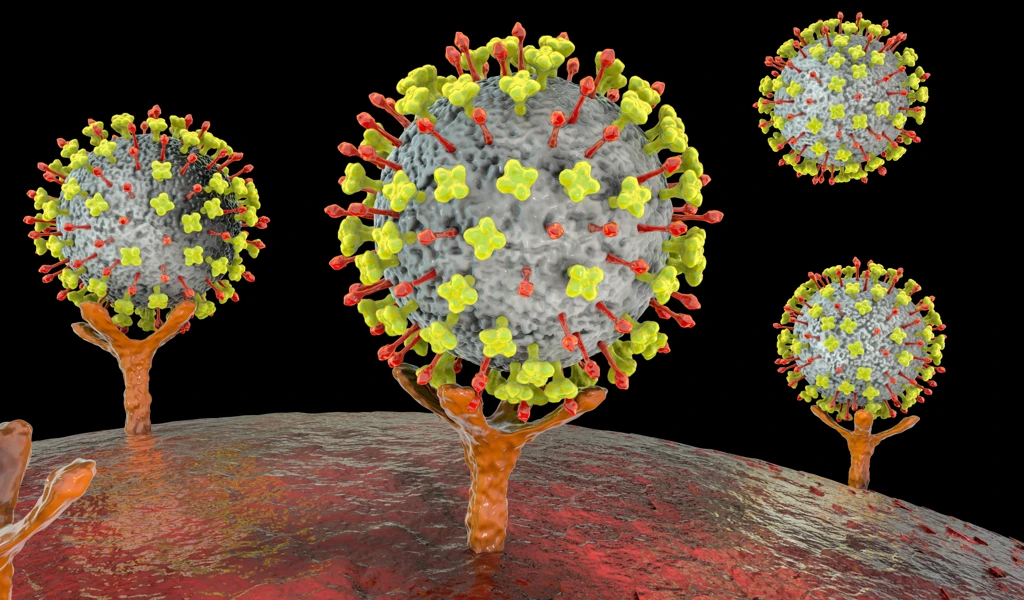

It has supported four early-stage Nipah vaccine candidates, two of which are in active development, and has also invested in the development of a Nipah virus monoclonal antibody (mAb).

A Nipah mAb is intended for use alongside vaccines during an outbreak. mAbs would serve as an immunological bridge - offering immediate protection before onset of longer-lasting vaccine-induced immunity - helping to contain viral spread.

To help prepare for the next Disease X, CEPI is also supporting the development of self-amplifying mRNA (saRNA) vaccine candidates with Pune-based Gennova. Gennova’s work will not only help establish the suitability of the saRNA platform for use against Nipah but also its suitability as part of a wider group of RNA technologies that could enable rapid responses to future Disease X threats that might emerge from the paramyxovirus viral family.

All experimental knowledge on Nipah virus acquired over the past two decades is derived from only two virus strains. Investments in surveillance, virus isolation, and sequencing can further our understanding of the impact of Nipah virus strain variation on medical countermeasure efficacy.

To that end, CEPI is also working with IEDCR and ICDDR,B in Bangladesh and the University of Malaya, Malaysia, to advance our immunological and epidemiological understanding of Nipah, which is currently limited by the scarcity of widely available sera from henipavirus survivors and by the fact that the long-term clinical effects of the disease have yet to be fully characterised. Research emerging from this partnership has reported long-term durability of immunity in Nipah virus survivors. The findings could help inform Nipah vaccine development by aiming to mimic this long-lasting protection.

CEPI also funded the establishment of the first WHO International Standard for anti-Nipah virus antibodies. The availability and use of this material as an International Standard will be invaluable in the standardisation of Nipah Virus serological assays.

Ultimately, investment in a combined portfolio of several medical countermeasures against Nipah, including surveillance systems, should be part of a coordinated, multilateral strategy for epidemic and pandemic preparedness given the unpredictability of Nipah outbreaks and the high case–fatality rate.

Latest Nipah news

AI-enhanced self-amplifying mRNA vaccine set to combat one of the deadliest known viruses

New human trials for novel antibody offer hope for immediate protection against deadly Nipah

Unmasking Nipah virus on a worldwide quest for insight and defence

What are monoclonal antibodies, and what role could they play in ending a potential pandemic?

CEPI awards contract worth up to US$ 31 million to The University of Tokyo to develop vaccine against Nipah virus

How climate change increases pandemic risk

Nipah - The Next Global Pandemic?

CEPI awards up to US$43.6 million to Public Health Vaccines, LLC. for development of a single-dose Nipah virus vaccine candidate

CEPI-funded Nipah virus vaccine candidate first to reach Phase 1 clinical trial

CEPI and Universiti Malaya announce new collaboration to advance Nipah virus research

Nipah virus: The deadly illness without a vaccine